Stress slows the immune response in sick mice

Cell Press | 04-28-2021

The neurotransmitter noradrenaline, which plays a key role in the fight-or-flight stress response, impairs immune responses by inhibiting the movements of various white blood cells in different tissues, researchers report April 28th in the journal Immunity. The fast and transient effect occurred in mice with infections and cancer, but for now, it’s unclear whether the findings generalize to humans with various health conditions.

“We found that stress can cause immune cells to stop moving and prevents immune cells from protecting against disease,” says senior study author University of Melbourne’s Scott Mueller (@SMuellerLab) of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute). “This is novel because it was not known that stress signals can stop immune cells from moving about in the body and performing their job.”

One main function of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is to coordinate the fight-or-flight stress response–a group of changes that prepare the body to fight or take flight in stressful or dangerous situations to protect itself from possible harm. Most tissues, including the lymph nodes and spleen, are innervated by SNS fibers. Stress-induced activation of the SNS can suppress immune responses, but the underlying mechanisms have been poorly characterized. “We hypothesized that SNS signals might modify the movement of T cells in tissues and lead to compromised immunity,” Mueller says.

White blood cells, also known as leukocytes, travel constantly throughout the body and are highly motile within tissues, where they locate and eradicate pathogens and tumors. Although the movement of leukocytes is critical for immunity, it has not been clear how these cells integrate various signals to navigate within tissues. “We also speculated that neurotransmitter signals might be a rapid way to modulate leukocyte behavior in tissues, in particular during acute stress that involves increased activation of the SNS,” Mueller says.

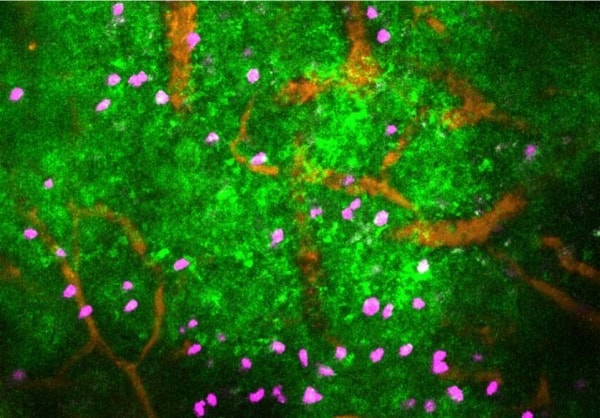

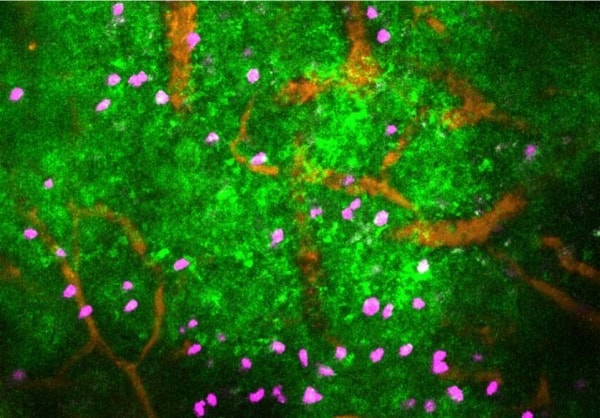

To test this idea, the researchers used advanced imaging to track the movements of T cells in mouse lymph nodes. Within minutes of being exposed to noradrenaline, T cells that had been rapidly moving stopped in their tracks and retracted their arm-like protrusions. This effect was transient, lasting between 45 and 60 minutes. Localized administration of noradrenaline in the lymph nodes of live mice also rapidly halted the cells. Similar effects were observed in mice that received noradrenaline infusions, which are used to treat patients with septic shock–a life-threatening condition that occurs when infection leads to dangerously low blood pressure. This finding suggests that therapeutic treatment with noradrenaline might impair leukocyte functions.

“We were very surprised that stress signals had such a rapid and dramatic effect on how immune cells move,” Mueller says. “Since movement is central to how immune cells can get to the right parts of the body and fight infections or tumors, this rapid movement off-switch was unexpected.”

Other experiments revealed that SNS signals inhibit the migration of distinct immune cells, including B cells and dendritic cells, exerting these effects in different tissues such as skin and liver. Additional results suggest that the effects of SNS activation on cell motility may be mediated by the constriction of blood vessels, reduced blood flow, and oxygen deprivation in tissues, resulting in an increase in calcium signaling in leukocytes.

“Our results reveal that an unanticipated consequence of modulation of blood flow in response to SNS activity is the rapid sensing of changes in oxygen by leukocytes and the inhibition of motility,” Mueller says. “Such rapid paralysis of leukocyte behavior identifies a physiological consequence of SNS activity that explains, at least in part, the widely observed relationship between stress and impaired immunity.”

Moreover, SNS signals impaired protective immunity against pathogens and tumors in various mouse models, decreasing the proliferation and expansion of T cells in the lymph nodes and spleen. For example, treatment with SNS-stimulating molecules rapidly stopped the movements of T cells and dendritic cells in mice infected with herpes simplex virus 1 and reduced virus-specific T cell recruitment to the site of the skin infection. Similar effects were observed in mice with melanoma and in mice infected with a malarial parasite.

“Our data suggest that SNS activity in tissues could impact immune outcomes in diverse diseases,” Mueller says. “Further insight into the impact of adrenergic receptor signals on cellular functions in tissues may inform the development of improved treatments for infections and cancer.”

The degree to which SNS activation affects leukocyte behavior or disease outcomes in humans remains to be determined. Notably, increased SNS activity is prominent in patients with obesity and heart failure, while psychological stress can cause blood vessel constriction in patients with heart disease. An unappreciated impact of increased SNS activity, particularly in individuals with underlying health conditions, might be impaired leukocyte behavior and functions. The findings may also have important health implications for patients who use SNS-activating drugs to treat diseases such as heart failure, sepsis, asthma, and allergic reactions.

Moving forward, the researchers will further examine the mechanisms by which immune cells are affected by SNS stress signals and explore relevant strategies to boost anti-cancer responses in patients. “This knowledge will allow us to test the impact of drugs that block the sympathetic stress pathway, such as beta-blockers, on the outcomes of vaccination and cancer treatments,” Mueller says. “These types of drugs might be safe treatment options for patients where stress could contribute to poor immune function.”

Source:

Materials provided by Cell Press. Content may be edited for clarity, style, and length.