Right gene expression program could turn immune cells into cancer killers

Johns Hopkins Medicine | 09-21-2021

Cancer-fighting immune cells in patients with lung cancer whose tumors do not respond to immunotherapies appear to be running on a different “program” that makes them less effective than immune cells in patients whose cancers respond to these immune treatments, suggests a new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

The findings, published in the August 5 issue of Nature, could lead to new ways to overcome tumor resistance to these treatments.

“Cancer immunotherapies have tremendous promise, but this promise only comes to fruition for a fraction of patients who receive them,” says study leader Kellie N. Smith, Ph.D., assistant professor of oncology and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute of Immunotherapy investigator. “Understanding why patients do or don’t respond could help us raise these numbers.”

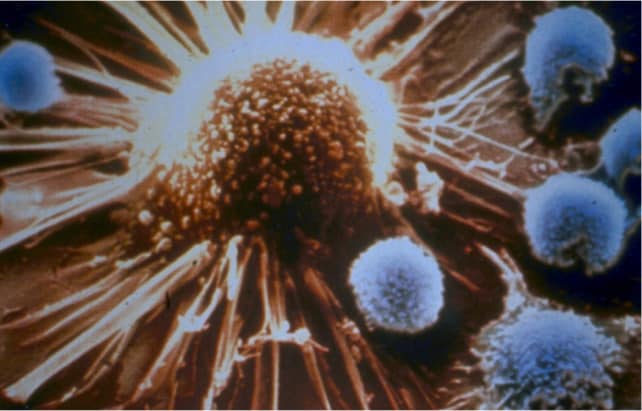

Cancer immunotherapies have gained traction in recent years as a way to harness the immune system’s inherent drive to rid the body of malignant cells, Smith explains. One prominent type of immunotherapy, known as checkpoint inhibitors, breaks down molecular defenses that allow cancer cells to masquerade as healthy cells, enabling immune cells known as CD8 T cells to attack the cancer cells. Different populations of these immune cells recognize specific aberrant proteins, which prompt them to kill malignant cells as well as cells infected by various viruses.

Although checkpoint inhibitors have shown tremendous success in some cancer types — even sometimes eradicating all evidence of disease — the portion of patients with these dramatic responses is relatively low. For example, only about a quarter of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have significant responses to these treatments.

Searching for differences between responders and nonresponders, Smith and her colleagues turned to results of a previous immunotherapy study. They gathered blood, tumor and healthy tissue samples taken from 20 early-stage NSCLC patients who took part in the previous study, which tested the effects of administering immune checkpoint inhibitors before surgery to remove tumors. Nine of the patients had a dramatic response to checkpoint inhibitors, with 10% or less of their original tumors remaining at the time of surgery. The other 11 patients were nonresponders and had either significantly lower responses or no response at all.

After isolating CD8 T cells from each of these samples, the researchers used a technology developed at Johns Hopkins called MANAFEST (Mutation Associated NeoAntigen Functional Expansion of Specific T cells) to search specifically for those cells that recognize proteins produced by cancerous mutations (known as mutation-associated neoantigens, or MANA), influenza or Epstein-Barr, the virus that causes infectious mononucleosis. They then analyzed these cells using a commercially available technique called single-cell transcriptomics to see which genes were actively producing proteins in individual cells — the “program” that these cells run on.

The researchers found that responders and nonresponders alike had similarly sized armies of CD8 T cells in their tumors, with similar numbers of cells in both populations that respond to MANA, influenza and Epstein-Barr. However, when they compared the transcriptional programs between responders and nonresponders, they found marked differences. MANA-oriented CD8 T cells from responders showed fewer markers of exhaustion than those in nonresponders, Smith explains. Responders’ CD8 cells were ready to fight when exposed to tumor proteins and produced fewer proteins that inhibit their activity, she says. In one patient who showed a complete response to checkpoint inhibitors — no evidence of active cancer by the time of surgery — the MANA-oriented CD8 T cells had been completely reprogrammed to serve as effective cancer killers. In contrast, nonresponders’ MANA-oriented CD8 T cells were sluggish, with significantly more inhibitory proteins produced.

Both responders and nonresponders’ MANA-, influenza- or Epstein-Barr-oriented CD8 T cells had significant differences in their programming as well. The MANA-oriented cells tended to be incompletely activated compared with the other CD8 T cell types. The MANA-oriented cells were also significantly less responsive to interleukin-7, a molecule that readies immune cells to fight, compared with influenza-oriented cells.

Together, Smith says, these findings suggest numerous differences in MANA-oriented cells between checkpoint inhibitor responders and nonresponders that could eventually serve as drug targets to make nonresponders’ CD8 T cells act more like responders’ — both for NSCLC and a broad array of other cancer types.

“By learning how to reprogram these immune cells, we could someday facilitate disease-free survival for more people with cancer,” says Smith. She adds that “an important and interesting finding was that nonresponders had cells that recognized the tumor. So there is ‘hope’ for developing treatments for patients who don’t respond to single agent immunotherapy. We just need to figure out the right target to activate these cells to help them do what they were made to do.”

Source:

Materials provided by Johns Hopkins Medicine. Content may be edited for clarity, style, and length.